Hidden verse: Joni Zwart on translating Roxane van Iperen’s ’t Hooge Nest

19 november 2019Nu in de winkel: Joni Zwarts vertaling van Roxane van Iperens ’t Hooge Nest: Sisters of Auschwitz. Voor ons licht ze haar vertaling toe.

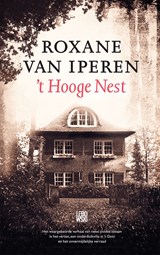

’t Hooge Nest (The High Nest) is a large house on a hill in the forests of Naarden, some twenty miles from Amsterdam. Roxane van Iperen and her husband bought this villa in 2012. As they began to renovate the house, they discovered trapdoors and hiding places everywhere. In the years that followed, Roxane, author and journalist, reconstructed the history of her new home, in particular the story of two young sisters who lived there in 1943 and 1944.

At the height of the Second World War, The High Nest sheltered dozens of resistance fighters and Jews – hence the trapdoors and hiding places. The safe house was run by Lien and Janny Brilleslijper, who both worked for the resistance themselves, and were Jewish. ‘This is what we believed in. We did what we had to do, what we could do,’ is what Janny, the youngest sister, said.

‘t Hooge Nest, published by Lebowski in November 2018, is the result of years of thorough research. Horrific historical facts come to life as Roxane van Iperen follows the sisters’ personal journey, which eventually leads to Auschwitz.

A few months ago, Roxane introduced me to another author with the words: ‘This is Joni, she’s translating ‘t Hooge Nest into English. Poor thing.’ She knew I still had to dive into the third part of the story, the brutal months in the camps. And indeed, I don’t think I have ever cried as much about a book as I have with this one. But oftentimes they were tears of awe. One sister reminding the other, simply by still being there: you are a person. We grew up together in Amsterdam and I love you. They might want to destroy you, but we won’t ever let them. Your life matters. You matter. We promised each other to survive, and we will.

Although in this series of articles it is often the first sentence of the book people focus on, I thought it might be appropriate to reveal a little secret about a phrase in the middle. It is no plot spoiler that The High Nest and its occupants are betrayed. An infamous Jew hunter, escorted by three other men, searches the house and literally throws each new person he finds into the living room.

Nadat er nog een uur was verstreken hoorden ze gestommel op de trap. De deur zwaaide open en Bram en Loes Teixeira de Mattos werden naar binnen gegooid, hun ogen dof en hun schouders gebogen.

After another hour had passed, they heard stumbling on the stairs. The door flung open and Bram and Loes Teixeira de Mattos were thrown into the room, bowed heads and lowered eyes.

The last seven words in Dutch are slightly different from the translation I chose to use. The original text literally says: ‘their eyes dull and their shoulders bent’. This is what happened: as I read the Dutch words and pictured the scene, a line from a song came to mind: bowed head and lowered eyes. The song is on the first album of Ben Harper, ‘Welcome to the Cruel World’ (1994), and is actually a poem by Maya Angelou, put to music. This poem is her famous ‘Still I Rise’, which begins like this:

'You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may trod me in the very dirt

But still, like dust, I’ll rise.'

And in the fourth stanza, we find:

'Did you want to see me broken?

Bowed head and lowered eyes?

Shoulders falling down like teardrops,

Weakened by my soulful cries?'

Followed by a few more stanzas, tied together with:

'Leaving behind nights of terror and fear

I rise

Into a daybreak that’s wondrously clear

I rise

Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave,

I am the dream and the hope of the slave.

I rise

I rise

I rise.'

Bram and Loes Teixeira de Mattos, two elderly people, are forcefully pushed into a room. They have just been caught, were probably beaten and were forcefully shouted at, hence the dull, dispirited look in their eyes. Their shoulders are bent, another sign of defeat, and also a way to protect the body against more pain, to defend whatever is left by making oneself small. This image must have conjured up the picture I had, not even consciously, connected to ‘bowed head and lowered eyes’ because the words instantly came up. And I decided to keep them. As a hidden homage to Maya Angelou and people like her, such as Janny and Lien, who did not let anyone break them and always rose strong.

In her acknowledgements at the end of the book, Roxane van Iperen says: ‘Immersing oneself in the details of the Holocaust for a long time profoundly changes a person, but I can draw on the strong will, courage and humour of the Brilleslijper sisters for the rest of my life.’ And then she cites writer and philosopher Albert Camus: ‘In the midst of winter I, at last, discovered that there was in me an invincible summer.’ Perhaps Camus's summer is not unlike the wondrously clear daybreak Maya Angelou describes.

Joni Zwart has translated samples of novels by authors such as Arnon Grunberg, Erik Jan Harmens and Ivo Victoria for their Dutch publishers to introduce them abroad. The Sisters of Auschwitz is the first complete book she translated into English.